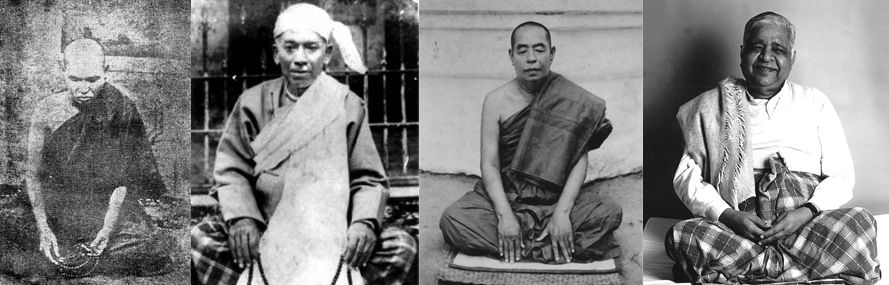

Vipassana Masters

Sixth century BC was an important era in history. This was the period when a great benefactor of mankind was born and became renowned as Gotama the Buddha. The Buddha rediscovered the path of Dhamma leading to the eradication of universal suffering. With great compassion he spent forty-five years showing the path and this helped millions of people to come out of their misery. Even today this path is helping humanity, and will continue to do so provided the teachings and practice are maintained in their pristine purity.

The following account of Sayagyi U Ba Khin’s teacher is partially based on a translation of the book “Saya Thetgyi” by Dhammacariya U Htay Hlaing, Myanmar.

Saya Thetgyi (pronounced “Sa ya ta ji” in Burmese) was born in the farming village of Pyawbwegyi, eight miles south of Rangoon, on the opposite side of the Rangoon river, on June 27, 1873. He was given the name Maung Po Thet. His father died when Po Thet was about 10, leaving his mother alone to care for the four children: him, his two brothers and a sister.

She supported the family by selling vegetable fritters in the village. The little boy was made to go around selling leftover fritters, but often came home without having sold any because he was too shy to advertise his wares by calling out. So his mother dispatched two children: Po Thet to carry the fritters on a tray on his head, and his younger sister to proclaim their wares.

Because he was needed to help support the family, his formal education was minimal -only about six years. His parents did not own any land or rice fields, and so used to collect the stalks of rice which remained after harvesting in the fields of others. One day on the way home from the fields, Po Thet found some small fish in a pond that was drying up. He caught them and brought them home so that he could release them into the village pond. His mother saw the fish and was about to chastise her son for catching them, but when he explained his intentions to her, she instead exclaimed, “Sadhu! Sadhu! (well-said! well-done!).” She was a kind-hearted woman who never nagged or scolded, but did not tolerate any akusala (immoral) deed.

When he was 14 years old, Maung Po Thet started working as a bullock-cart driver transporting rice, giving his daily wages to his mother. He was so small at the time that he had to take a box along to help him get in and out of the cart.

Po Thet’s next job was as a sampan oarsman. The village of Pyawbwegyi is on a flat cultivated plain, fed by many tributaries which flow into the Rangoon river. When the rice fields are flooded navigation is a problem, and one of the common means of travel is by these long, flat-bottomed boats.

The owner of a local rice mill observed the small boy working diligently carrying loads of rice, and decided to hire him as a tally-man in the mill at a wage of six rupees per month. Po Thet lived by himself in the mill and ate simple meals of split pea fritters and rice.

At first he bought rice from the Indian watchman and other laborers. They told him he could help himself to the sweepings of milled rice which were kept for pig and chicken feed. Po Thet refused, saying that he did not want to take the rice without the mill owner’s knowledge. The owner found out, however, and gave his permission. As it happened, Maung Po Thet did not have to eat the rice debris for long. Soon the sampan and cart owners began to give him rice because he was such a helpful and willing worker. Still, Po Thet continued to collect the sweepings, giving them to poor villagers who could not afford to buy rice.

After one year his salary was increased to 10 rupees, and after two years, to 15. The mill owner offered him money to buy good quality rice and allowed him free milling of 100 baskets per month. His monthly salary increased to 25 rupees, which supported him and his mother quite adequately.

Maung Po Thet married Ma Hmyin when he was about 16 years old, as was customary. His wife was the youngest of three daughters of a well-to-do landowner and rice merchant. The couple had two children, a daughter and a son. Following the Burmese custom, they lived in a joint family with Ma Hmyin’s parents and sisters. Ma Yin, the younger sister, remained single and managed a successful small business. She was later instrumental in supporting U Po Thet in practicing and teaching meditation.

Ma Hmyin’s eldest sister, Ma Khin, married Ko Kaye and had a son, Maung Nyunt. Ko Kaye managed the family rice fields and business. Maung Po Thet, now called U Po Thet or U Thet (Mr. Thet), also prospered in the buying and selling of rice.

As a child, U Thet had not had the opportunity to ordain as a novice monk, which is an important and common practice in Burma. It was only when his nephew Maung Nyunt became a novice at 12 years of age that U Thet himself became a novice. Later, for a time, he also ordained as a bhikkhu (monk).

When he was about 23, he learned Anapana meditation from a lay teacher, Saya Nyunt, and continued to practice for seven years.

U Thet and his wife had many friends and relatives living nearby in the village. With numerous uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces, cousins and in-laws, they led an idyllic life of contentment in the warmth and harmony of family and friends.

This rustic peace and happiness was shattered when a cholera epidemic struck the village in 1903. Many villagers died, some within a few days. They included U Thet’s son and young teenage daughter who, it is said, died in his arms. His brother-in-law, Ko Kaye, and his wife also perished from the disease, as well as U Thet’s niece who was his daughter’s playmate.

This calamity affected U Thet deeply, and he could not find refuge anywhere. Desperately wanting to find a way out of this misery, he asked permission from his wife and sister-in-law, Ma Yin, and other relatives to leave the village in search of “the deathless.”

Accompanied in his wanderings by a devoted companion and follower, U Nyo, U Thet wandered all over Burma in a fervent search, visiting mountain retreats and forest monasteries, studying with different teachers, both monks and laymen. Finally he followed the suggestion of his first teacher, Saya Nyunt, to go north to Monywa to practice with the Venerable Ledi Sayadaw.

During these years of spiritual searching, U Thet’s wife and sister-in-law remained in Pyawbwegyi and managed the rice fields. In the first few years he returned occasionally to see that all was well. Finding that the family was prospering, he began to meditate more continuously. He stayed with Ledi Sayadaw seven years in all, during which time his wife and sister-in-law supported him by sending money each year from the harvest on the family farm.

With U Nyo, he finally went back to his village, but did not return to his former householder’s life. Ledi Sayadaw had advised him at the time of his departure to work diligently to develop his samadhi (concentration) and panna (purifying wisdom), so that eventually he could begin to teach meditation.

Accordingly, when U Thet and U Nyo reached Pyawbwegyi, they went straight to the sala (rest-house) at the edge of the family farm, which they began to use as a Dhamma hall. Here they meditated continuously. They arranged for a woman who lived nearby to cook two meals a day while they kept up their retreat.

U Thet persevered in this way for one year, making rapid progress in his meditation. At the end of the period he felt the need for advice from his teacher, and although he could not speak to Ledi Sayadaw in person, he knew that his teacher’s books were in a cupboard at his home. So he went there to consult the manuals.

His wife and her sister, in the meantime, had become quite angry with him for not returning to the house after such a long absence. His wife had even decided to divorce him. When the sisters saw U Po Thet approaching, they agreed neither to greet nor welcome him. But as soon as he came in the door, they found themselves welcoming him profusely. They talked awhile and U Thet asked for their forgiveness, which they readily granted.

They served him tea and a meal and he procured his books. He explained to his wife that he was now living on eight precepts and would not be returning to the usual householder’s life; from now on they would be as brother and sister.

His wife and sister-in-law invited him to come to the house every day for his morning meal and happily agreed to continue supporting him. He was extremely grateful for their generosity and told them that the only way he could repay them was to give them Dhamma.

Other relatives, including his wife’s cousin, U Ba Soe, came to see and talk with him. After about two weeks, U Thet said that he was spending too much time coming and going for lunch, so Ma Hmyin and Ma Yin offered to send the noon meal to the sala.

Misinterpreting U Thet’s zeal, people in the village were at first reluctant to come to him for instruction. They thought that due perhaps to grief over his losses, and his absence from the village, he had lost his senses. But slowly they realized from his speech and actions that he was indeed a transformed person, one who was living in accordance with Dhamma.

Soon some of U Thet’s relatives and friends began to request that he teach them meditation. U Ba Soe offered to take charge of the fields and the household affairs and U Thet’s sister and a niece took responsibility for preparing the meals. U Thet started teaching Anapana to a group of about 15 people in 1914, when he was 41 years old. The students all stayed at the sala, some of them going home from time to time. He gave discourses to his meditation students, as well as to interested people who were not practicing meditation. His listeners found his talks so learned that they refused to believe that U Thet had very little theoretical knowledge of Dhamma.

Due to his wife’s and sister-in-law’s generous financial support and the help of other family members, all the food and other necessities were provided for the meditators who came to U Thet’s Dhamma hall, even to the extent, on one occasion, of compensating workers for wages lost while they took a Vipassana course.

In about 1915, after teaching for a year, U Thet took his wife and her sister and a few other family members to Monywa to pay respects to Ledi Sayadaw who was then about 70 years old. When U Thet told his teacher about his meditation experiences and the courses he had been offering, Ledi Sayadaw was very pleased.

It was during this visit that Ledi Sayadaw gave his walking staff to U Thet, saying: “Here my great pupil, take my staff and forward. Keep it well. I do not give this to you to make you live long, but as a reward, so that there will be no mishaps in your life. You have been successful. From today onwards you must teach the Dhamma of rupa and nama (mind and matter) to 6,000 people. The Dhamma known by you is inexhaustible, so propagate the sasana (era of the Buddha’s teaching). Pay homage to the sasana in my stead.”

The next day Ledi Sayadaw summoned all the monks of his monastery. He requested U Thet to stay on for 10 or 15 days to instruct them. The Sayadaw then told the gathering bhikkhus: “Take note, all of you. This layman is my great pupil U Po Thet, from lower Burma. He is capable of teaching meditation like me. Those of you who wish to practice meditation, follow him. Learn the technique from him and practice. You, Dayaka Thet (a lay supporter of a monk who undertakes to supply his needs such as food, robes, medicine, etc.), hoist the victory banner of Dhamma in place of me, starting at my monastery.”

U Thet then taught Vipassana meditation to about 25 monks learned in the scriptures. It was at this time that he became known as Saya Thetgyyi (saya means “teacher”; gyi is a suffix denoting respect).

Ledi Sayadaw encouraged Saya Thetgyi to teach the Dhamma on his behalf. Saya Thetgyi knew many of Ledi Sayadaw’s prolific writings by heart, and was able to expound on the Dhamma with references to the scriptures in such a way that most learned Sayadaws (monk teachers) could not find fault. Ledi Sayadaw’s exhortation to him to teach Vipassana in his stead was a solemn responsibility, but Saya Thetgyi was apprehensive due to his lack of theoretical knowledge. Bowing to his teacher in deep respect, he said: “Among your pupils, I am the least learned in the scriptures. To dispense the sasana by teaching Vipassana as decreed by you is a highly subtle, yet heavy duty to perform, sir. That is why I request that, if at any time I need to ask for clarification, you will give me your help and guidance. Please be my support, and please admonish me whenever necessary.”

Ledi Sayadaw reassured him by replying, “I will not forsake you, even at the time of my passing away.”

Saya Thetgyi and his relatives returned to their village in southern Burma and discussed with other family members plans for carrying out the task given by Ledi Sayadaw. Saya Thetgyi considered traveling around Burma, thinking that he would have more contact with people that way. But his sister-in-law said, “You have a Dhamma hall here, and we can support you in your work by preparing food for the students. Why not stay and give courses? There are many who will come here to learn Vipassana.” He agreed, and began holding regular courses at his sala in Pyawbwegyi.

As his sister-in-law had predicted, many people started coming, and Saya Thetgyi’s reputation as a meditation teacher spread. He taught simple farmers and laborers, as well as those who were well-versed in the Pali texts. The village was not far from Rangoon, the capital of Burma under the British, so government employees and city dwellers like U Ba Khin, also came.

As more and more people came to learn meditation, Saya Thetgyi appointed as assistant teachers some of the older, experienced meditators like U Nyo, U Ba Soe, and U Aung Nyunt.

The center progressed year by year until there were up to 200 students, including monks and nuns, in the courses. There was not enough room in the Dhamma hall, so the more experienced students practiced meditation in their homes and came to the sala only for the discourses.

From the time he returned from Ledi Sayadaw’s center, Saya Thetgyi lived by himself and ate only one meal a day, in solitude and silence. Like the bhikkhus, he never discussed his meditation attainments. If questioned, he would never say what stage of meditation he or any other student had achieved, although it was widely believed in Burma that he was an Anagami (person having achieved the last stage before final liberation), and he was known as Anagam Saya Thetgyi.

Since lay teachers of Vipassana were rare at that time, Saya Thetgyi faced certain difficulties that monk teachers did not. For example, he was opposed by some because he was not so learned in the scriptures. Saya Thetgyi simply ignored these criticisms and allowed the results of the practice to speak for themselves.

For 30 years he taught meditation to all who came to him, guided by his own experience and using Ledi Sayadaw’s manuals as a reference. By 1945, when he was 72, he had fulfilled his mission of teaching thousands. His wife had died, his sister-in-law had become paralyzed, and his own health was failing. So he distributed all his property to his nieces and nephews, setting aside 50 acres of rice fields for the maintenance of his Dhamma hall.

He had 20 water buffaloes that had tilled his fields for years. He distributed them among people who he knew would treat them kindly, and sent them off with the invocation, “You have been my benefactors. Thanks to you, the rice has been grown. Now you are free from your work. May you be released from this kind of life for a better existence.”

Saya Thetgyi moved to Rangoon, both for medical treatment and to see his students there. He told some of them that he would die in Rangoon and that his body would be cremated in a place where no cremation had taken place before. He also said that his ashes should not be kept in holy places because he was not entirely free from defilements, that is, he was not an arahant (fully enlightened being).

One of his students had established a meditation center at Arzanigone, on the northern slope of the Shwedagon Pagoda. Nearby was a bomb shelter that had been built during the Second World War. Saya Thetgyi used this shelter as his meditation cave. At night he stayed with one of his assistant teachers. His students from Rangoon, including the Accountant General, U Ba Khin, and Commissioner of Income Tax, U San Thein, visited him as much as time permitted.

He instructed all who came to see him to be diligent in their practice, to treat the monks and nuns who came to practice meditation with respect, to be well-disciplined in body, speech and mind, and to pay respects to the Buddha in everything they did.

Saya Thetgyi was accustomed to go to the Shwedagon Pagoda every evening, but after about a week he caught a cold and fever from sitting in the dug-out shelter. Despite being treated by physicians, his condition deteriorated. As his state worsened, his nieces and nephews came from Pyawbwegyi to Rangoon. Every night his students, numbering about 50, sat in meditation together. During these group meditations Saya Thetgyi himself did not say anything, but silently meditated.

One night at about 10 pm, Saya Thetgyi was with a number of his students (U Ba Khin was unable to be present). He was lying on his back, and his breathing became loud and prolonged. Two of the students were watching intently, while the rest meditated silently. At exactly 11:00 p.m., his breathing became deeper. It seemed as if each inhalation and expiration took about five minutes. After three breaths of this kind the breathing stopped altogether, and Saya Thetgyi passed away.

His body was cremated on the northern slope of the Shwedagon Pagoda and Sayagyi U Ba Khin and his disciples later built a small pagoda on the spot. But perhaps the most fitting and enduring memorial to this singular teacher is the fact that the task given him by Ledi Sayadaw of spreading the Dhamma in all strata of society still continues.

The Venerable Ledi Sayadaw* was born in 1846 in Saing-pyin village, Dipeyin township, in the Shwebo district (currently Monywa district) of Northern Burma. His childhood name was Maung Tet Khaung. (Maung is the Burmese title for boys and young men, equivalent to master, Tet means climbing upward and Khaung means roof or summit.) It proved to be an appropriate name, since young Maung Tet Khaung, indeed, climbed to the summit in all his endeavors.

In his village he attended the traditional monastery school where the bhikkhus (monks) taught children to read and write in Burmese as well as recite Pali text. Because of these ubiquitous monastery schools, Burma has traditionally maintained a very high rate of literacy.

At the age of eight he began to study with his first teacher, U Nanda-dhaja Sayadaw, and he ordained as a samanera(novice) under the same Sayadaw at the age of fifteen. He was given the name Nana-dhaja (the banner of knowledge). His monastic education included Pali grammar and various texts from the Pali canon with a specialty in Abhidhammattha-sangaha, a commentary which serves as a guide to the Abhidhamma** section of the canon.

Later in life he wrote a somewhat controversial commentary on Abhidhammattha-sangaha, called Paramattha-dipani (Manual of Ultimate Truth) in which he corrected certain mistakes he had found in the earlier and, at that time, accepted commentary on that work. His corrections were eventually accepted by the bhikkhus and his work became the standard reference.

During his days as a samanera, in the middle part of the nineteenth century, before modern lighting, he would routinely study the written texts during the day and join the bhikkhus and other samaneras in recitation from memory after dark. Working in this way he mastered the Abhidhamma texts.

When he was 18, Samanera Nana-dhaja briefly left the robes and returned to his life as a layman. He had become dissatisfied with his education, feeling it was too narrowly restricted to the Tipitaka+. After about six months his first teacher and another influential teacher, Myinhtin Sayadaw, sent for him and tried to persuade him to return to the monastic life; but he refused.

Myinhtin Sayadaw suggested that he should at least continue with his education. The young Maung Tet Khaung was very bright and eager to learn, so he readily agreed to this suggestion.

“Would you be interested in learning the Vedas, the ancient sacred writings of Hinduism?” asked Myinhtin Sayadaw.

“Yes, venerable sir,” answered Maung Tet Khaung.

“Well, then you must become a samanera,” the Sayadaw replied, “otherwise Sayadaw U Gandhama of Yeu village will not take you as his student.”

“I will become a samanera,” he agreed.

In this way he returned to the life of a novice, never to leave the robes of a monk again. Later on, he confided to one of his disciples, “At first I was hoping to earn a living with the knowledge of the Vedas by telling peoples’ fortunes. But I was more fortunate in that I became a samanera again. My teachers were very wise; with their boundless love and compassion, they saved me.”

The brilliant Samanera Nana-dhaja, under the care of Gandhama Sayadaw, mastered the Vedas in eight months and continued his study of the Tipitaka. At the age of 20, on April 20, 1866, he took the higher ordination to become a bhikkhuunder his old teacher U Nanda-dhaja Sayadaw, who became his preceptor (one who gives the precepts).

In 1867, just prior to the monsoon retreat, Bhikkhu Nana-dhaja left his preceptor and the Monywa district where he had grown up, in order to continue his studies in Mandalay.

At that time, during the reign of King Min Don Min who ruled from 1853-1878, Mandalay was the royal capital of Burma and the most important center of learning in the country. He studied under several of the leading Sayadaws and learned lay scholars as well. He resided primarily in the Maha-Jotikarama Monastery and studied with Ven. San-Kyaung Sayadaw, a teacher who is famous in Burma for translating the Visuddhimagga Path of Purification into Burmese.

During this time, the Ven. San-Kyaung Sayadaw gave an examination of 20 questions for 2000 students. Bhikkhu Nana-dhaja was the only one who was able to answer all the questions satisfactorily. These answers were later published in 1880, under the title Parami-dipani (Manual of Perfections), the first of many books written in Pali and Burmese by the Ven. Ledi Sayadaw.

During the time of his studies in Mandalay King Min Don Min sponsored the Fifth Council, calling bhikkhus from far and wide to recite and purify the Tipitika. The council was held in Mandalay in 1871 and the authenticated texts were carved into 729 marble slabs that stand today, each slab housed under a small pagoda surrounding the golden Kuthodaw Pagoda at the foot of Mandalay Hill. At this council, Bhikkhu Nana-dhaja helped in the editing and translating of the Abhidhamma texts.

After eight years as a bhikkhu, having passed all his examinations, the Ven. Nana-dhaja was qualified as a teacher of introductory Pali at the Maha-Jotikarama Monastery where he had been studying.

For eight more years he remained there, teaching and continuing his own scholastic endeavors, until 1882 when he moved to Monywa. He was now 36 years old. At that time Monywa was a small district center on the east bank of the Chindwin River, which was renowned as a place where the teaching method included the entire Tipitika, rather than selected portions only.

To teach Pali to the bhikkhus and samaneras at Monywa, he came into town during the day, but in the evening he would cross to the west bank of the Chindwin River and spend the nights in meditation in a small vihara (monastery) on the side of Lak-pan-taung Mountain. Although we do not have any definitive information, it seems likely that this was the period when he began practicing Vipassana in the traditional Burmese way: with attention to Anapana (respiration) and vedana (sensation).

The British conquered upper Burma in 1885 and sent the last king, Thibaw, who ruled from 1878-1885, into exile. The next year, 1886, Ven.Nana-dhaja went into retreat in Ledi Forest, just to the north of Monywa. After a while, many bhikkhus started coming to him there, requesting that he teach them. A monastery was built to house them and named Ledi-tawya Monastery. From this monastery he took the name by which he is best known: Ledi Sayadaw. It is said that one of the main reasons Monywa grew to be a large town, as it is today, was that so many people were attracted to Ledi Sayadaw’s monastery. While he taught many aspiring students at Ledi-tawya, he continued his practice of retiring to his small cottage vihara across the river for his own meditation.

When he had been in the Ledi Forest Monastery for over ten years, his main scholastic works began to be published. The first was Paramattha-dipani (Manual of Ultimate Truth) mentioned above, published in 1897. His second book of this period was Nirutta-dipani, a book on Pali grammar. Because of these books he gained a reputation as one of the most learned bhikkhus in Burma.

Though Ledi Sayadaw was based at the Ledi-tawya monastery, at times he traveled throughout Burma, teaching both meditation and scripture. He is, indeed, a rare example of a bhikkhu who was able to excel in pariyatti (the theory of Dhamma) as well as patipatti (the practice of Dhamma). It was during these trips throughout Burma that many of his published works were written. For example, he wrote the Paticca-samuppada-dipani in two days while traveling by boat from Mandalay to Prome. He had with him no reference books, but, because he had a thorough knowledge of the Tipiitaka, he needed none. In the Manuals of Buddhism there are 76 manuals, commentaries, essays, and so on, listed under his authorship, but even this is an incomplete list of his works.

Later, he also wrote many books on Dhamma in Burmese. He said he wanted to write in such a way that even a simple farmer could understand. Before his time, it was unusual to write on Dhamma subjects so that lay people would have access to them. Even while teaching orally, the bhikkhus would commonly recite long passages in Pali and then translate them literally, which was very hard for ordinary people to understand. It must have been the strength of Ledi Sayadaw’s practical understanding and the resultant metta (loving-kindness) that overflowed in his desire to spread Dhamma to all levels of society. His Paramattha-sankhepa, a book of 2,000 Burmese verses which translates the Abhidhammattha-sangaha, was written for young people and is still very popular today. His followers started many associations which promoted the learning of Abhidhamma by using this book.

In his travels around Burma, Ledi Sayadaw also discouraged the consumption of cow meat. He wrote a book called Go-mamsa-matika which urged people not to kill cows for food and encouraged a vegetarian diet.

It was during this period, just after the turn of the century, that the Ven. Ledi Sayadaw was first visited by U Po Thet who learned Vipassana from him and subsequently became one of the most well-known lay meditation teachers in Burma, and the teacher of Sayagi U Ba Khin, Goenkaji’s teacher.

By 1911 his reputation both as a scholar and meditation master had grown to such an extent that the British government of India, which also ruled Burma, conferred on him the title of Aggamaha-pandita (foremost great scholar). He was also awarded a Doctorate of Literature from the University of Rangoon. During the years 1913-1917 he had a correspondence with Mrs. Rhys-Davids of the Pali Text Society in London, and translations of several of his discussions on points of Abhidhamma were published in the Journal of the Pali Text Society.

In the last years of his life the Ven. Ledi Sayadaw’s eyesight began to fail him because of the years he had spent reading, studying and writing, often with poor illumination. At the age of 73 he became blind and devoted the remaining years of his life exclusively to meditating and teaching meditation. He died in 1923 at the age of 77 at Pyinmana, between Mandalay and Rangoon, in one of the many monasteries that had been founded in his name as a result of his travels and teaching all over Burma.

The Venerable Ledi Sayadaw was perhaps the most outstanding Buddhist figure of his age. All who have come in contact with the path of Dhamma in recent years owe a great debt of gratitude to this scholarly, saintly monk who was instrumental in reviving the traditional practice of Vipassana, making it more available for renunciates and lay people alike. In addition to this most important aspect of his teaching, his concise, clear and extensive scholarly work served to clarify the experiential aspect of Dhamma.

*The title Sayadaw, meaning venerable teacher, was originally given to important elder monks (Theras) who instructed the king in Dhamma. Later, it became a title for highly respected monks in general.

**Abhidhamma is the third section of the Pali canon in which the Buddha gave profound, detailed and technical descriptions of the reality of mind and matter.

+Tipitaka is the Pali name for the entire canon. It means three baskets, i.e., the basket of the Vinaya (rules for the monks); the basket of the Suttas (discourses); and the basket of the Abhidhamma (see footnote 2, above).

“Dhamma eradicates suffering and gives happiness. Who gives this happiness? It is not the Buddha but the Dhamma, the knowledge of anicca within the body, which gives the happiness. That is why you must meditate and be aware of anicca continually.” – Sayagyi U Ba Khin

Sayagyi U Ba Khin was born in Rangoon, the capital of Burma, on 6th March, 1899. He was the younger of two children in a family of modest means living in a working class district. Burma was ruled by Britain at the time, as it was until after the Second World War. Learning English was therefore very important; in fact, job advancement depended on having a good speaking knowledge of English.

Fortunately, an elderly man from a nearby factory assisted U Ba Khin in entering the Methodist Middle School at the age of eight. He proved a gifted student. He had the ability to commit his lessons to memory, learning his English grammar book by heart from cover to cover. He was first in every class and earned a middle school scholarship. A Burmese teacher helped him gain entrance to St. Paul’s Institution, where every year he was again at the head of his high school class.

In March of 1917, he passed the final high school examination, winning a gold medal as well as a college scholarship. But family pressures forced him to discontinue his formal education to start earning money.

His first job was with a Burmese newspaper called The Sun, but after some time he began working as an accounts clerk in the office of the Accountant General of Burma. Few other Burmese were employed in this office since most of the civil servants in Burma at the time were British or Indian. In 1926 he passed the Accounts Service examination, given by the provincial government of India. In 1937, when Burma was separated from India, he was appointed the first Special Office Superintendent.

It was on 1st January, 1937, that Sayagyi tried meditation for the first time. A student of Saya Thetgyi – a wealthy farmer and meditation teacher – was visiting U Ba Khin and explained Anapana meditation to him. When Sayagyi tried it, he experienced good concentration, which impressed him so much that he resolved to complete a full course. Accordingly, he applied for a ten-day leave of absence and set out for Saya Thetgyi’s teaching centre.

It is a testament to U Ba Khin’s determination to learn Vipassana that he left the headquarters on short notice. His desire to meditate was so strong that only one week after trying Anapana, he was on his way to Saya Thetgyi’s centre at Pyawbwegyi.

The small village of Pyawbwegyi is due south of Rangoon, across the Rangoon River and miles of rice paddies. Although it is only eight miles from the city, the muddy fields before harvest time make it seem longer; travellers must cross the equivalent of a shallow sea. When U Ba Khin crossed the Rangoon River, it was low tide, and the sampan boat he hired could only take him to Phyarsu village–about half the distance –along a tributary which connected to Pyawbwegyi. Sayagyi climbed the river bank, sinking in mud up to his knees. He covered the remaining distance on foot across the fields, arriving with his legs caked in mud.

That same night, U Ba Khin and another Burmese student, who was a disciple of Ledi Sayadaw, received Anapana instructions from Saya Thetgyi. The two students advanced rapidly, and were given Vipassana the next day. Sayagyi progressed well during this first ten-day course, and continued his work during frequent visits to his teacher’s centre and meetings with Saya Thetgyi whenever he came to Rangoon.

When he returned to his office, Sayagyi found an envelope on his desk. He feared that it might be a dismissal note but found, to his surprise, that it was a promotion letter. He had been chosen for the post of Special Office Superintendent in the new office of the Auditor General of Burma.

In 1941, a seemingly happenstance incident occurred which was to be important in Sayagyi’s life. While on government business in upper Burma, he met by chance Webu Sayadaw, a monk who had achieved high attainments in meditation. Webu Sayadaw was impressed with U Ba Khin’s proficiency in meditation, and urged him to teach. He was the first person to exhort Sayagyi to start teaching. An account of this historic meeting, and subsequent contacts between these two important figures, is described in the article Ven. Webu Sayadaw and Sayagyi U Ba Khin.

U Ba Khin did not begin teaching in a formal way until about a decade after he first met Webu Sayadaw. Saya Thetgyi also encouraged him to teach Vipassana. On one occasion during the Japanese occupation of Burma, Saya Thetgyi came to Rangoon and stayed with one of his students who was a government official. When his host and other students expressed a wish to see Saya Thetgyi more often, he replied, “I am like the doctor who can only see you at certain times. But U Ba Khin is like the nurse who will see you any time.”

Sayagyi’s government service continued for another twenty-six years. He became Accountant General on 4th January, 1948, the day Burma gained independence. For the next two decades, he was employed in various capacities in the government, most of the time holding two or more posts, each equivalent to the head of a department. At one time he served as head of three separate departments simultaneously for three years and, on another occasion, head of four departments for about one year. When he was appointed as the chairman of the State Agricultural Marketing Board in 1956, the Burmese government conferred on him the title of “Thray Sithu,” a high honorary title. Only the last four years of Sayagyi’s life were devoted exclusively to teaching meditation. The rest of the time he combined his skill in meditation with his devotion to government service and his responsibilities to his family. Sayagyi was a married householder with five daughters and one son.

In 1950 he founded the Vipassana Association of the Accountant General’s Office where lay people, mainly employees of that office, could learn Vipassana. In 1952, the International Meditation Centre (I.M.C.) was opened in Rangoon, two miles north of the famous Shwedagon Pagoda. Here many Burmese and foreign students had the good fortune to receive instruction in the Dhamma from Sayagyi.

Sayagyi was active in the planning for the Sixth Council known as Chatta Sangayana (Sixth Recitation) which was held in 1954-56 in Rangoon. Sayagyi was a founding member in 1950 of two organizations which were later merged to become the Union of Burma Buddha Sasana Council (U.B.S.C.), the main planning body for the Great Council. U Ba Khin served as an executive member of the U.B.S.C. and as chairman of the committee for patipatti (practice of meditation).

He also served as honorary auditor of the Council and was therefore responsible for maintaining the accounts for all dana (donation) receipts and expenditures. There was an extensive building programme spread over 170 acres to provide housing, dining areas and kitchen, a hospital, library, museum, four hostels and administrative buildings. The focal point of the entire enterprise was the Maha Pasanaguha (Great Cave), a massive hall where approximately five thousand monks from Burma, Sri Lanka, Thailand, India, Cambodia and Laos gathered to recite, purify, edit and publish the Tipitaka (scriptures). The monks, working in groups, prepared the Pali texts for publication, comparing the Burmese, Sri Lankan Thai, and Cambodian editions and the Roman-script edition of the Pali Text Society in London. The corrected and approved texts were recited in the Great Cave. Ten to fifteen thousand lay men and women came to listen to the recitations of the monks.

To efficiently handle the millions in donations that came for this undertaking, U Ba Khin created a system of printing receipt books on different coloured paper for different amounts of dana, ranging from the humblest donation up to very large amounts. Only selected people were allowed to handle the larger contributions, and every donation was scrupulously accounted for, avoiding any hint of misappropriation.

Sayagyi remained active with the U.B.S.C. in various capacities until 1967. In this way he combined his responsibilities and talents as a layman and government official with his strong Dhamma volition to spread the teaching of Buddha. In addition to the prominent public service he gave to that cause, he continued to teach Vipassana regularly at his centre. Some of the Westerners who came to the Sixth Council were referred to Sayagyi for instruction in meditation since at that time there was no other teacher of Vipassana who was fluent in English.

Because of his highly demanding government duties, Sayagyi was only able to teach a small number of students. Many of his Burmese students were connected with his government work. Many Indian students were introduced by S N Goenka. Sayagyi’s students from abroad were small in number but diverse, including leading Western Buddhists, academicians, and members of the diplomatic community in Rangoon.

From time to time, Sayagyi was invited to address foreign audiences in Burma on the subject of Dhamma. On one occasion, for example, he was asked to deliver a series of lectures at the Methodist Church in Rangoon. These lectures were published as a booklet titled “What Buddhism is.” Copies were distributed to Burmese embassies and various Buddhist organisations around the world. This booklet attracted a number of Westerners to attend courses with Sayagyi. On another occasion he delivered a lecture to a group of press representatives from Israel, who were in Burma on the occasion of the visit of Israel’s prime minister, David Ben Gurion. This lecture was later published under the title “The Real Values of True Buddhist Meditation.”

Sayagyi finally retired from his outstanding career in government service in 1967. From that time, until his death in 1971, he stayed at I.M.C., teaching Vipassana. Shortly before his death he thought back to all those who had helped him – the old man who had helped him start school, the Burmese teacher who helped him join St. Paul’s and, among many others, one friend whom he had lost sight of over forty years earlier and now found mentioned in the local newspaper. He dictated letters addressed to this old friend and to some foreign students and disciples, including Dr. S.N. Goenka. On the 18th of January, Sayagyi suddenly became ill. When his newly rediscovered friend received Sayagyi’s letter on the 20th, he was shocked to read Sayagyi’s death announcement in the same post.

Shri S.N. Goenka was in India conducting a course when news of his teacher’s death reached him. He sent a telegram back to I.M.C. which contained the famous Pali verse:

Anicca vata sankhara, uppadavaya-dhammino.

Uppajjitva nirujjhanti, tesam vupasamo sukho.

Impermanent truly are compounded things, by nature arising and passing away.

If they arise and are extinguished, their eradication brings happiness.

One year later, in a tribute to his teacher, Mr. S.N. Goenka wrote: “Even after his passing away one year ago, observing the continued success of the courses, I get more and more convinced that it is his metta (loving-kindness) force which is giving me all the inspiration and strength to serve so many people – Obviously the force of Dhamma is immeasurable.”

Sayagyi’s aspirations are being accomplished. The Buddha’s teachings, carefully preserved all these centuries, are still being practiced, and are still bringing results here and now.

S.N. Goenka, or Goenkaji as he is widely and respectfully referred to, is well known in numerous countries of the world as a master teacher of meditation. He received the technique that he teaches in the 1950’s from Sayagyi U Ba Khin of Burma, who in turn received it from Saya Thet, who received it in turn from the venerable monk, Ledi Sayadaw, who in turn received it from his own teacher in a long line of teachers descended directly from the Buddha. The achievement of this line of teachers in preserving the technique through such a long period of time is extraordinary, and a cause for gratitude in those who practise it. Now, in a world hungry for inner peace, there has been an extraordinary spread of the technique in Goenkaji’s lifetime.

In spite of his magnetic personality and the enormous success of his teaching methods, Goenkaji gives all credit for his success to the efficacy of Dhamma itself. He has never sought to play the role of a guru or to found any kind of sect, cult or religious organisation. When teaching the technique he never omits to say that he received it from the Buddha through a chain of teachers down to his own teacher, and his gratitude to them for the benefits that he has personally gained in his own meditation is evident. At the same time, he continually emphasises that he does not teach Buddhism or any kind of “ism,” and that the technique that he teaches is universal, for people from any religious or philosophical background or belief.

Although his family was from India, Goenkaji was brought up in Burma, where he learnt the technique from his teacher Sayagyi U Ba Khin. After being authorised as a teacher by U Ba Khin he left Burma in 1969 in response to his mother’s illness, to give a ten-day course to his parents and twelve others in Bombay. The inspiration that he imparted and the extraordinary results of his teaching led to many more such courses, first in campsites around India and then later in centres as these began to spring up. From 1979 onwards he also started giving courses outside India, notably in Sri Lanka, Thailand, Nepal, France, England, North America, Japan, Australia, and New Zealand. All of these countries today have one or more centres.

- Saya Thetgyi

-

The following account of Sayagyi U Ba Khin’s teacher is partially based on a translation of the book “Saya Thetgyi” by Dhammacariya U Htay Hlaing, Myanmar.

Saya Thetgyi (pronounced “Sa ya ta ji” in Burmese) was born in the farming village of Pyawbwegyi, eight miles south of Rangoon, on the opposite side of the Rangoon river, on June 27, 1873. He was given the name Maung Po Thet. His father died when Po Thet was about 10, leaving his mother alone to care for the four children: him, his two brothers and a sister.

She supported the family by selling vegetable fritters in the village. The little boy was made to go around selling leftover fritters, but often came home without having sold any because he was too shy to advertise his wares by calling out. So his mother dispatched two children: Po Thet to carry the fritters on a tray on his head, and his younger sister to proclaim their wares.

Because he was needed to help support the family, his formal education was minimal -only about six years. His parents did not own any land or rice fields, and so used to collect the stalks of rice which remained after harvesting in the fields of others. One day on the way home from the fields, Po Thet found some small fish in a pond that was drying up. He caught them and brought them home so that he could release them into the village pond. His mother saw the fish and was about to chastise her son for catching them, but when he explained his intentions to her, she instead exclaimed, “Sadhu! Sadhu! (well-said! well-done!).” She was a kind-hearted woman who never nagged or scolded, but did not tolerate any akusala (immoral) deed.

When he was 14 years old, Maung Po Thet started working as a bullock-cart driver transporting rice, giving his daily wages to his mother. He was so small at the time that he had to take a box along to help him get in and out of the cart.

Po Thet’s next job was as a sampan oarsman. The village of Pyawbwegyi is on a flat cultivated plain, fed by many tributaries which flow into the Rangoon river. When the rice fields are flooded navigation is a problem, and one of the common means of travel is by these long, flat-bottomed boats.

The owner of a local rice mill observed the small boy working diligently carrying loads of rice, and decided to hire him as a tally-man in the mill at a wage of six rupees per month. Po Thet lived by himself in the mill and ate simple meals of split pea fritters and rice.

At first he bought rice from the Indian watchman and other laborers. They told him he could help himself to the sweepings of milled rice which were kept for pig and chicken feed. Po Thet refused, saying that he did not want to take the rice without the mill owner’s knowledge. The owner found out, however, and gave his permission. As it happened, Maung Po Thet did not have to eat the rice debris for long. Soon the sampan and cart owners began to give him rice because he was such a helpful and willing worker. Still, Po Thet continued to collect the sweepings, giving them to poor villagers who could not afford to buy rice.

After one year his salary was increased to 10 rupees, and after two years, to 15. The mill owner offered him money to buy good quality rice and allowed him free milling of 100 baskets per month. His monthly salary increased to 25 rupees, which supported him and his mother quite adequately.

Maung Po Thet married Ma Hmyin when he was about 16 years old, as was customary. His wife was the youngest of three daughters of a well-to-do landowner and rice merchant. The couple had two children, a daughter and a son. Following the Burmese custom, they lived in a joint family with Ma Hmyin’s parents and sisters. Ma Yin, the younger sister, remained single and managed a successful small business. She was later instrumental in supporting U Po Thet in practicing and teaching meditation.

Ma Hmyin’s eldest sister, Ma Khin, married Ko Kaye and had a son, Maung Nyunt. Ko Kaye managed the family rice fields and business. Maung Po Thet, now called U Po Thet or U Thet (Mr. Thet), also prospered in the buying and selling of rice.

As a child, U Thet had not had the opportunity to ordain as a novice monk, which is an important and common practice in Burma. It was only when his nephew Maung Nyunt became a novice at 12 years of age that U Thet himself became a novice. Later, for a time, he also ordained as a bhikkhu (monk).

When he was about 23, he learned Anapana meditation from a lay teacher, Saya Nyunt, and continued to practice for seven years.

U Thet and his wife had many friends and relatives living nearby in the village. With numerous uncles, aunts, nephews, nieces, cousins and in-laws, they led an idyllic life of contentment in the warmth and harmony of family and friends.

This rustic peace and happiness was shattered when a cholera epidemic struck the village in 1903. Many villagers died, some within a few days. They included U Thet’s son and young teenage daughter who, it is said, died in his arms. His brother-in-law, Ko Kaye, and his wife also perished from the disease, as well as U Thet’s niece who was his daughter’s playmate.

This calamity affected U Thet deeply, and he could not find refuge anywhere. Desperately wanting to find a way out of this misery, he asked permission from his wife and sister-in-law, Ma Yin, and other relatives to leave the village in search of “the deathless.”

Accompanied in his wanderings by a devoted companion and follower, U Nyo, U Thet wandered all over Burma in a fervent search, visiting mountain retreats and forest monasteries, studying with different teachers, both monks and laymen. Finally he followed the suggestion of his first teacher, Saya Nyunt, to go north to Monywa to practice with the Venerable Ledi Sayadaw.

During these years of spiritual searching, U Thet’s wife and sister-in-law remained in Pyawbwegyi and managed the rice fields. In the first few years he returned occasionally to see that all was well. Finding that the family was prospering, he began to meditate more continuously. He stayed with Ledi Sayadaw seven years in all, during which time his wife and sister-in-law supported him by sending money each year from the harvest on the family farm.

With U Nyo, he finally went back to his village, but did not return to his former householder’s life. Ledi Sayadaw had advised him at the time of his departure to work diligently to develop his samadhi (concentration) and panna (purifying wisdom), so that eventually he could begin to teach meditation.

Accordingly, when U Thet and U Nyo reached Pyawbwegyi, they went straight to the sala (rest-house) at the edge of the family farm, which they began to use as a Dhamma hall. Here they meditated continuously. They arranged for a woman who lived nearby to cook two meals a day while they kept up their retreat.

U Thet persevered in this way for one year, making rapid progress in his meditation. At the end of the period he felt the need for advice from his teacher, and although he could not speak to Ledi Sayadaw in person, he knew that his teacher’s books were in a cupboard at his home. So he went there to consult the manuals.

His wife and her sister, in the meantime, had become quite angry with him for not returning to the house after such a long absence. His wife had even decided to divorce him. When the sisters saw U Po Thet approaching, they agreed neither to greet nor welcome him. But as soon as he came in the door, they found themselves welcoming him profusely. They talked awhile and U Thet asked for their forgiveness, which they readily granted.

They served him tea and a meal and he procured his books. He explained to his wife that he was now living on eight precepts and would not be returning to the usual householder’s life; from now on they would be as brother and sister.

His wife and sister-in-law invited him to come to the house every day for his morning meal and happily agreed to continue supporting him. He was extremely grateful for their generosity and told them that the only way he could repay them was to give them Dhamma.

Other relatives, including his wife’s cousin, U Ba Soe, came to see and talk with him. After about two weeks, U Thet said that he was spending too much time coming and going for lunch, so Ma Hmyin and Ma Yin offered to send the noon meal to the sala.

Misinterpreting U Thet’s zeal, people in the village were at first reluctant to come to him for instruction. They thought that due perhaps to grief over his losses, and his absence from the village, he had lost his senses. But slowly they realized from his speech and actions that he was indeed a transformed person, one who was living in accordance with Dhamma.

Soon some of U Thet’s relatives and friends began to request that he teach them meditation. U Ba Soe offered to take charge of the fields and the household affairs and U Thet’s sister and a niece took responsibility for preparing the meals. U Thet started teaching Anapana to a group of about 15 people in 1914, when he was 41 years old. The students all stayed at the sala, some of them going home from time to time. He gave discourses to his meditation students, as well as to interested people who were not practicing meditation. His listeners found his talks so learned that they refused to believe that U Thet had very little theoretical knowledge of Dhamma.

Due to his wife’s and sister-in-law’s generous financial support and the help of other family members, all the food and other necessities were provided for the meditators who came to U Thet’s Dhamma hall, even to the extent, on one occasion, of compensating workers for wages lost while they took a Vipassana course.

In about 1915, after teaching for a year, U Thet took his wife and her sister and a few other family members to Monywa to pay respects to Ledi Sayadaw who was then about 70 years old. When U Thet told his teacher about his meditation experiences and the courses he had been offering, Ledi Sayadaw was very pleased.

It was during this visit that Ledi Sayadaw gave his walking staff to U Thet, saying: “Here my great pupil, take my staff and forward. Keep it well. I do not give this to you to make you live long, but as a reward, so that there will be no mishaps in your life. You have been successful. From today onwards you must teach the Dhamma of rupa and nama (mind and matter) to 6,000 people. The Dhamma known by you is inexhaustible, so propagate the sasana (era of the Buddha’s teaching). Pay homage to the sasana in my stead.”

The next day Ledi Sayadaw summoned all the monks of his monastery. He requested U Thet to stay on for 10 or 15 days to instruct them. The Sayadaw then told the gathering bhikkhus: “Take note, all of you. This layman is my great pupil U Po Thet, from lower Burma. He is capable of teaching meditation like me. Those of you who wish to practice meditation, follow him. Learn the technique from him and practice. You, Dayaka Thet (a lay supporter of a monk who undertakes to supply his needs such as food, robes, medicine, etc.), hoist the victory banner of Dhamma in place of me, starting at my monastery.”

U Thet then taught Vipassana meditation to about 25 monks learned in the scriptures. It was at this time that he became known as Saya Thetgyyi (saya means “teacher”; gyi is a suffix denoting respect).

Ledi Sayadaw encouraged Saya Thetgyi to teach the Dhamma on his behalf. Saya Thetgyi knew many of Ledi Sayadaw’s prolific writings by heart, and was able to expound on the Dhamma with references to the scriptures in such a way that most learned Sayadaws (monk teachers) could not find fault. Ledi Sayadaw’s exhortation to him to teach Vipassana in his stead was a solemn responsibility, but Saya Thetgyi was apprehensive due to his lack of theoretical knowledge. Bowing to his teacher in deep respect, he said: “Among your pupils, I am the least learned in the scriptures. To dispense the sasana by teaching Vipassana as decreed by you is a highly subtle, yet heavy duty to perform, sir. That is why I request that, if at any time I need to ask for clarification, you will give me your help and guidance. Please be my support, and please admonish me whenever necessary.”

Ledi Sayadaw reassured him by replying, “I will not forsake you, even at the time of my passing away.”

Saya Thetgyi and his relatives returned to their village in southern Burma and discussed with other family members plans for carrying out the task given by Ledi Sayadaw. Saya Thetgyi considered traveling around Burma, thinking that he would have more contact with people that way. But his sister-in-law said, “You have a Dhamma hall here, and we can support you in your work by preparing food for the students. Why not stay and give courses? There are many who will come here to learn Vipassana.” He agreed, and began holding regular courses at his sala in Pyawbwegyi.

As his sister-in-law had predicted, many people started coming, and Saya Thetgyi’s reputation as a meditation teacher spread. He taught simple farmers and laborers, as well as those who were well-versed in the Pali texts. The village was not far from Rangoon, the capital of Burma under the British, so government employees and city dwellers like U Ba Khin, also came.

As more and more people came to learn meditation, Saya Thetgyi appointed as assistant teachers some of the older, experienced meditators like U Nyo, U Ba Soe, and U Aung Nyunt.

The center progressed year by year until there were up to 200 students, including monks and nuns, in the courses. There was not enough room in the Dhamma hall, so the more experienced students practiced meditation in their homes and came to the sala only for the discourses.

From the time he returned from Ledi Sayadaw’s center, Saya Thetgyi lived by himself and ate only one meal a day, in solitude and silence. Like the bhikkhus, he never discussed his meditation attainments. If questioned, he would never say what stage of meditation he or any other student had achieved, although it was widely believed in Burma that he was an Anagami (person having achieved the last stage before final liberation), and he was known as Anagam Saya Thetgyi.

Since lay teachers of Vipassana were rare at that time, Saya Thetgyi faced certain difficulties that monk teachers did not. For example, he was opposed by some because he was not so learned in the scriptures. Saya Thetgyi simply ignored these criticisms and allowed the results of the practice to speak for themselves.

For 30 years he taught meditation to all who came to him, guided by his own experience and using Ledi Sayadaw’s manuals as a reference. By 1945, when he was 72, he had fulfilled his mission of teaching thousands. His wife had died, his sister-in-law had become paralyzed, and his own health was failing. So he distributed all his property to his nieces and nephews, setting aside 50 acres of rice fields for the maintenance of his Dhamma hall.

He had 20 water buffaloes that had tilled his fields for years. He distributed them among people who he knew would treat them kindly, and sent them off with the invocation, “You have been my benefactors. Thanks to you, the rice has been grown. Now you are free from your work. May you be released from this kind of life for a better existence.”

Saya Thetgyi moved to Rangoon, both for medical treatment and to see his students there. He told some of them that he would die in Rangoon and that his body would be cremated in a place where no cremation had taken place before. He also said that his ashes should not be kept in holy places because he was not entirely free from defilements, that is, he was not an arahant (fully enlightened being).

One of his students had established a meditation center at Arzanigone, on the northern slope of the Shwedagon Pagoda. Nearby was a bomb shelter that had been built during the Second World War. Saya Thetgyi used this shelter as his meditation cave. At night he stayed with one of his assistant teachers. His students from Rangoon, including the Accountant General, U Ba Khin, and Commissioner of Income Tax, U San Thein, visited him as much as time permitted.

He instructed all who came to see him to be diligent in their practice, to treat the monks and nuns who came to practice meditation with respect, to be well-disciplined in body, speech and mind, and to pay respects to the Buddha in everything they did.

Saya Thetgyi was accustomed to go to the Shwedagon Pagoda every evening, but after about a week he caught a cold and fever from sitting in the dug-out shelter. Despite being treated by physicians, his condition deteriorated. As his state worsened, his nieces and nephews came from Pyawbwegyi to Rangoon. Every night his students, numbering about 50, sat in meditation together. During these group meditations Saya Thetgyi himself did not say anything, but silently meditated.

One night at about 10 pm, Saya Thetgyi was with a number of his students (U Ba Khin was unable to be present). He was lying on his back, and his breathing became loud and prolonged. Two of the students were watching intently, while the rest meditated silently. At exactly 11:00 p.m., his breathing became deeper. It seemed as if each inhalation and expiration took about five minutes. After three breaths of this kind the breathing stopped altogether, and Saya Thetgyi passed away.

His body was cremated on the northern slope of the Shwedagon Pagoda and Sayagyi U Ba Khin and his disciples later built a small pagoda on the spot. But perhaps the most fitting and enduring memorial to this singular teacher is the fact that the task given him by Ledi Sayadaw of spreading the Dhamma in all strata of society still continues.

- Ledi Sayadaw

-

The Venerable Ledi Sayadaw* was born in 1846 in Saing-pyin village, Dipeyin township, in the Shwebo district (currently Monywa district) of Northern Burma. His childhood name was Maung Tet Khaung. (Maung is the Burmese title for boys and young men, equivalent to master, Tet means climbing upward and Khaung means roof or summit.) It proved to be an appropriate name, since young Maung Tet Khaung, indeed, climbed to the summit in all his endeavors.

In his village he attended the traditional monastery school where the bhikkhus (monks) taught children to read and write in Burmese as well as recite Pali text. Because of these ubiquitous monastery schools, Burma has traditionally maintained a very high rate of literacy.

At the age of eight he began to study with his first teacher, U Nanda-dhaja Sayadaw, and he ordained as a samanera(novice) under the same Sayadaw at the age of fifteen. He was given the name Nana-dhaja (the banner of knowledge). His monastic education included Pali grammar and various texts from the Pali canon with a specialty in Abhidhammattha-sangaha, a commentary which serves as a guide to the Abhidhamma** section of the canon.

Later in life he wrote a somewhat controversial commentary on Abhidhammattha-sangaha, called Paramattha-dipani (Manual of Ultimate Truth) in which he corrected certain mistakes he had found in the earlier and, at that time, accepted commentary on that work. His corrections were eventually accepted by the bhikkhus and his work became the standard reference.

During his days as a samanera, in the middle part of the nineteenth century, before modern lighting, he would routinely study the written texts during the day and join the bhikkhus and other samaneras in recitation from memory after dark. Working in this way he mastered the Abhidhamma texts.

When he was 18, Samanera Nana-dhaja briefly left the robes and returned to his life as a layman. He had become dissatisfied with his education, feeling it was too narrowly restricted to the Tipitaka+. After about six months his first teacher and another influential teacher, Myinhtin Sayadaw, sent for him and tried to persuade him to return to the monastic life; but he refused.

Myinhtin Sayadaw suggested that he should at least continue with his education. The young Maung Tet Khaung was very bright and eager to learn, so he readily agreed to this suggestion.

“Would you be interested in learning the Vedas, the ancient sacred writings of Hinduism?” asked Myinhtin Sayadaw.

“Yes, venerable sir,” answered Maung Tet Khaung.

“Well, then you must become a samanera,” the Sayadaw replied, “otherwise Sayadaw U Gandhama of Yeu village will not take you as his student.”

“I will become a samanera,” he agreed.

In this way he returned to the life of a novice, never to leave the robes of a monk again. Later on, he confided to one of his disciples, “At first I was hoping to earn a living with the knowledge of the Vedas by telling peoples’ fortunes. But I was more fortunate in that I became a samanera again. My teachers were very wise; with their boundless love and compassion, they saved me.”

The brilliant Samanera Nana-dhaja, under the care of Gandhama Sayadaw, mastered the Vedas in eight months and continued his study of the Tipitaka. At the age of 20, on April 20, 1866, he took the higher ordination to become a bhikkhuunder his old teacher U Nanda-dhaja Sayadaw, who became his preceptor (one who gives the precepts).

In 1867, just prior to the monsoon retreat, Bhikkhu Nana-dhaja left his preceptor and the Monywa district where he had grown up, in order to continue his studies in Mandalay.

At that time, during the reign of King Min Don Min who ruled from 1853-1878, Mandalay was the royal capital of Burma and the most important center of learning in the country. He studied under several of the leading Sayadaws and learned lay scholars as well. He resided primarily in the Maha-Jotikarama Monastery and studied with Ven. San-Kyaung Sayadaw, a teacher who is famous in Burma for translating the Visuddhimagga Path of Purification into Burmese.

During this time, the Ven. San-Kyaung Sayadaw gave an examination of 20 questions for 2000 students. Bhikkhu Nana-dhaja was the only one who was able to answer all the questions satisfactorily. These answers were later published in 1880, under the title Parami-dipani (Manual of Perfections), the first of many books written in Pali and Burmese by the Ven. Ledi Sayadaw.

During the time of his studies in Mandalay King Min Don Min sponsored the Fifth Council, calling bhikkhus from far and wide to recite and purify the Tipitika. The council was held in Mandalay in 1871 and the authenticated texts were carved into 729 marble slabs that stand today, each slab housed under a small pagoda surrounding the golden Kuthodaw Pagoda at the foot of Mandalay Hill. At this council, Bhikkhu Nana-dhaja helped in the editing and translating of the Abhidhamma texts.

After eight years as a bhikkhu, having passed all his examinations, the Ven. Nana-dhaja was qualified as a teacher of introductory Pali at the Maha-Jotikarama Monastery where he had been studying.

For eight more years he remained there, teaching and continuing his own scholastic endeavors, until 1882 when he moved to Monywa. He was now 36 years old. At that time Monywa was a small district center on the east bank of the Chindwin River, which was renowned as a place where the teaching method included the entire Tipitika, rather than selected portions only.

To teach Pali to the bhikkhus and samaneras at Monywa, he came into town during the day, but in the evening he would cross to the west bank of the Chindwin River and spend the nights in meditation in a small vihara (monastery) on the side of Lak-pan-taung Mountain. Although we do not have any definitive information, it seems likely that this was the period when he began practicing Vipassana in the traditional Burmese way: with attention to Anapana (respiration) and vedana (sensation).

The British conquered upper Burma in 1885 and sent the last king, Thibaw, who ruled from 1878-1885, into exile. The next year, 1886, Ven.Nana-dhaja went into retreat in Ledi Forest, just to the north of Monywa. After a while, many bhikkhus started coming to him there, requesting that he teach them. A monastery was built to house them and named Ledi-tawya Monastery. From this monastery he took the name by which he is best known: Ledi Sayadaw. It is said that one of the main reasons Monywa grew to be a large town, as it is today, was that so many people were attracted to Ledi Sayadaw’s monastery. While he taught many aspiring students at Ledi-tawya, he continued his practice of retiring to his small cottage vihara across the river for his own meditation.

When he had been in the Ledi Forest Monastery for over ten years, his main scholastic works began to be published. The first was Paramattha-dipani (Manual of Ultimate Truth) mentioned above, published in 1897. His second book of this period was Nirutta-dipani, a book on Pali grammar. Because of these books he gained a reputation as one of the most learned bhikkhus in Burma.

Though Ledi Sayadaw was based at the Ledi-tawya monastery, at times he traveled throughout Burma, teaching both meditation and scripture. He is, indeed, a rare example of a bhikkhu who was able to excel in pariyatti (the theory of Dhamma) as well as patipatti (the practice of Dhamma). It was during these trips throughout Burma that many of his published works were written. For example, he wrote the Paticca-samuppada-dipani in two days while traveling by boat from Mandalay to Prome. He had with him no reference books, but, because he had a thorough knowledge of the Tipiitaka, he needed none. In the Manuals of Buddhism there are 76 manuals, commentaries, essays, and so on, listed under his authorship, but even this is an incomplete list of his works.

Later, he also wrote many books on Dhamma in Burmese. He said he wanted to write in such a way that even a simple farmer could understand. Before his time, it was unusual to write on Dhamma subjects so that lay people would have access to them. Even while teaching orally, the bhikkhus would commonly recite long passages in Pali and then translate them literally, which was very hard for ordinary people to understand. It must have been the strength of Ledi Sayadaw’s practical understanding and the resultant metta (loving-kindness) that overflowed in his desire to spread Dhamma to all levels of society. His Paramattha-sankhepa, a book of 2,000 Burmese verses which translates the Abhidhammattha-sangaha, was written for young people and is still very popular today. His followers started many associations which promoted the learning of Abhidhamma by using this book.

In his travels around Burma, Ledi Sayadaw also discouraged the consumption of cow meat. He wrote a book called Go-mamsa-matika which urged people not to kill cows for food and encouraged a vegetarian diet.

It was during this period, just after the turn of the century, that the Ven. Ledi Sayadaw was first visited by U Po Thet who learned Vipassana from him and subsequently became one of the most well-known lay meditation teachers in Burma, and the teacher of Sayagi U Ba Khin, Goenkaji’s teacher.

By 1911 his reputation both as a scholar and meditation master had grown to such an extent that the British government of India, which also ruled Burma, conferred on him the title of Aggamaha-pandita (foremost great scholar). He was also awarded a Doctorate of Literature from the University of Rangoon. During the years 1913-1917 he had a correspondence with Mrs. Rhys-Davids of the Pali Text Society in London, and translations of several of his discussions on points of Abhidhamma were published in the Journal of the Pali Text Society.

In the last years of his life the Ven. Ledi Sayadaw’s eyesight began to fail him because of the years he had spent reading, studying and writing, often with poor illumination. At the age of 73 he became blind and devoted the remaining years of his life exclusively to meditating and teaching meditation. He died in 1923 at the age of 77 at Pyinmana, between Mandalay and Rangoon, in one of the many monasteries that had been founded in his name as a result of his travels and teaching all over Burma.

The Venerable Ledi Sayadaw was perhaps the most outstanding Buddhist figure of his age. All who have come in contact with the path of Dhamma in recent years owe a great debt of gratitude to this scholarly, saintly monk who was instrumental in reviving the traditional practice of Vipassana, making it more available for renunciates and lay people alike. In addition to this most important aspect of his teaching, his concise, clear and extensive scholarly work served to clarify the experiential aspect of Dhamma.

*The title Sayadaw, meaning venerable teacher, was originally given to important elder monks (Theras) who instructed the king in Dhamma. Later, it became a title for highly respected monks in general.

**Abhidhamma is the third section of the Pali canon in which the Buddha gave profound, detailed and technical descriptions of the reality of mind and matter.

+Tipitaka is the Pali name for the entire canon. It means three baskets, i.e., the basket of the Vinaya (rules for the monks); the basket of the Suttas (discourses); and the basket of the Abhidhamma (see footnote 2, above).

- Sayagyi U Ba Khin

-

“Dhamma eradicates suffering and gives happiness. Who gives this happiness? It is not the Buddha but the Dhamma, the knowledge of anicca within the body, which gives the happiness. That is why you must meditate and be aware of anicca continually.” – Sayagyi U Ba Khin

Sayagyi U Ba Khin was born in Rangoon, the capital of Burma, on 6th March, 1899. He was the younger of two children in a family of modest means living in a working class district. Burma was ruled by Britain at the time, as it was until after the Second World War. Learning English was therefore very important; in fact, job advancement depended on having a good speaking knowledge of English.

Fortunately, an elderly man from a nearby factory assisted U Ba Khin in entering the Methodist Middle School at the age of eight. He proved a gifted student. He had the ability to commit his lessons to memory, learning his English grammar book by heart from cover to cover. He was first in every class and earned a middle school scholarship. A Burmese teacher helped him gain entrance to St. Paul’s Institution, where every year he was again at the head of his high school class.

In March of 1917, he passed the final high school examination, winning a gold medal as well as a college scholarship. But family pressures forced him to discontinue his formal education to start earning money.

His first job was with a Burmese newspaper called The Sun, but after some time he began working as an accounts clerk in the office of the Accountant General of Burma. Few other Burmese were employed in this office since most of the civil servants in Burma at the time were British or Indian. In 1926 he passed the Accounts Service examination, given by the provincial government of India. In 1937, when Burma was separated from India, he was appointed the first Special Office Superintendent.

It was on 1st January, 1937, that Sayagyi tried meditation for the first time. A student of Saya Thetgyi – a wealthy farmer and meditation teacher – was visiting U Ba Khin and explained Anapana meditation to him. When Sayagyi tried it, he experienced good concentration, which impressed him so much that he resolved to complete a full course. Accordingly, he applied for a ten-day leave of absence and set out for Saya Thetgyi’s teaching centre.

It is a testament to U Ba Khin’s determination to learn Vipassana that he left the headquarters on short notice. His desire to meditate was so strong that only one week after trying Anapana, he was on his way to Saya Thetgyi’s centre at Pyawbwegyi.

The small village of Pyawbwegyi is due south of Rangoon, across the Rangoon River and miles of rice paddies. Although it is only eight miles from the city, the muddy fields before harvest time make it seem longer; travellers must cross the equivalent of a shallow sea. When U Ba Khin crossed the Rangoon River, it was low tide, and the sampan boat he hired could only take him to Phyarsu village–about half the distance –along a tributary which connected to Pyawbwegyi. Sayagyi climbed the river bank, sinking in mud up to his knees. He covered the remaining distance on foot across the fields, arriving with his legs caked in mud.

That same night, U Ba Khin and another Burmese student, who was a disciple of Ledi Sayadaw, received Anapana instructions from Saya Thetgyi. The two students advanced rapidly, and were given Vipassana the next day. Sayagyi progressed well during this first ten-day course, and continued his work during frequent visits to his teacher’s centre and meetings with Saya Thetgyi whenever he came to Rangoon.

When he returned to his office, Sayagyi found an envelope on his desk. He feared that it might be a dismissal note but found, to his surprise, that it was a promotion letter. He had been chosen for the post of Special Office Superintendent in the new office of the Auditor General of Burma.

In 1941, a seemingly happenstance incident occurred which was to be important in Sayagyi’s life. While on government business in upper Burma, he met by chance Webu Sayadaw, a monk who had achieved high attainments in meditation. Webu Sayadaw was impressed with U Ba Khin’s proficiency in meditation, and urged him to teach. He was the first person to exhort Sayagyi to start teaching. An account of this historic meeting, and subsequent contacts between these two important figures, is described in the article Ven. Webu Sayadaw and Sayagyi U Ba Khin.

U Ba Khin did not begin teaching in a formal way until about a decade after he first met Webu Sayadaw. Saya Thetgyi also encouraged him to teach Vipassana. On one occasion during the Japanese occupation of Burma, Saya Thetgyi came to Rangoon and stayed with one of his students who was a government official. When his host and other students expressed a wish to see Saya Thetgyi more often, he replied, “I am like the doctor who can only see you at certain times. But U Ba Khin is like the nurse who will see you any time.”

Sayagyi’s government service continued for another twenty-six years. He became Accountant General on 4th January, 1948, the day Burma gained independence. For the next two decades, he was employed in various capacities in the government, most of the time holding two or more posts, each equivalent to the head of a department. At one time he served as head of three separate departments simultaneously for three years and, on another occasion, head of four departments for about one year. When he was appointed as the chairman of the State Agricultural Marketing Board in 1956, the Burmese government conferred on him the title of “Thray Sithu,” a high honorary title. Only the last four years of Sayagyi’s life were devoted exclusively to teaching meditation. The rest of the time he combined his skill in meditation with his devotion to government service and his responsibilities to his family. Sayagyi was a married householder with five daughters and one son.

In 1950 he founded the Vipassana Association of the Accountant General’s Office where lay people, mainly employees of that office, could learn Vipassana. In 1952, the International Meditation Centre (I.M.C.) was opened in Rangoon, two miles north of the famous Shwedagon Pagoda. Here many Burmese and foreign students had the good fortune to receive instruction in the Dhamma from Sayagyi.